Baby Hair: A Cultural Connection or a Conformist Curse?

There is Nothing Good About Needing Laid Edges to Be “Bad”

**This essay will appear in two parts because 1) I have too many thoughts and 2) you deserve some sort of organizational structure.**

A few years ago, one of my students came up to me in between classes. Inevitably, every year I will have one or two students (and some I don’t even teach) that become my year-long parasite. I long ago stopped trying to fight it, accepting that whatever that student needs from me by being in my shadow for that time, I’m willing to give them the shade.

I was straightening my desks between classes and halfway listening as she spouted off a litany of grievances…against her ex-best friend (they were back bestied the next week)…against the Assistant Principal (whom she still greeted cheerfully every morning at breakfast)…against her ex (who apparently can’t stay out her snap stories since she “blocked” him). I made the usual noises of affirmation, and then she said…

“Ms. Smith, you so pretty, but if you let me lay your edges, you’d be so bad!”

That gave me pause.

So then, I responded by saying “I can’t be ‘bad’ without laid edges?”

“Oh yeah! That’s not what I meant. I just meant that it would just pull it all together because you know your face card don’t ever decline!”

After she explained what that meant, I continued to press (pun completely intended) by asking why I should have to pretend that my hair does something it naturally does not want to do to be ‘bad’? That’s not good.

“Dang Ms. Smith, why you always gotta make everything philosophical or somethin’. I’m just trying to help you get a man so you can have a pretty baby and give me a sister.”

The audacity! For her to assume I’d need her help in “getting a man” is ridiculous, and it also (sadly) shows how used to “grown-folks business” this child really was, because no way in hell would I ever make such a suggestion to a teacher or any grown person for that matter. After reminding her that 1) my love life is off limits, 2) I have no children, and 3) she needs to go to class because I’m not writing her a pass, I sat down and thought about what she said. This sophomore clearly understood the link between texturism and preferences, although she could not clearly articulate it, and was urging me to buy into that stock, assuming my value would increase if the amount of gel on my edges did.

Hair as an Indicator of Blackness

Thinking on this later, I tried to get to the root of that icky feeling I could not shake since that conversation. I read some books, some articles, and some professional thinkers’ thoughts, and what I originally had just guessed as being true was confirmed; texturism is a bigger problem than colorism.

Shocking right? So many of us have been raised on paper-bag tests and “would you be in the house or in the fields” conjecture, that hair has seemingly become secondary to skin color.

Emma Dabiri, author of Don’t Touch My Hair

And then it all made sense: we’ve grown up as baby heirs because White Supremacy raised us, and hair is a more potent indicator of race than skin color. There are many people from East Asia, South Asia, South and Central America, and Australia with skin as dark as mine, but with hair like Silk. In Emma Dabiri’s Don’t Touch My Hair, she cites Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson when she pens that during slavery,

“…it was hair texture more than skin color that distinguished Africans specifically as degenerate…an African Albino is still read as black due to their hair and features. There are East Asian and South Asians who have darker complexions than some Africans and who are certainly darker-skinned than many African Americans and African Caribbeans, yet they are not ‘black’.”

In other words, Kinky hair is the only thing exclusively indicative of African roots, and it can oftentimes afford a dark-skinned person with light-skinned privilege in many parts of the word.

A Black Indigenous Woman from Australia, a Black Woman with Albinism, a Dark-Skinned Indian Woman

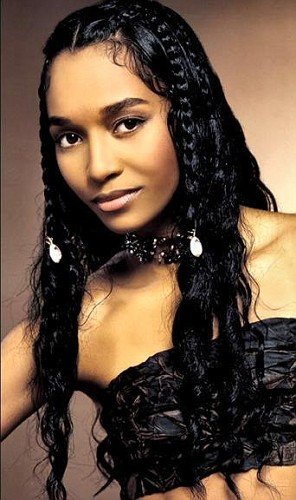

I’m not sure why this came as such a surprise to me. Years ago, I created an experiment for a unit I was teaching on Racism, Colorism, Featurism and Texturism. (These are the kinds of discussions you can have when you teach at an all-Black school). I put up a series of pictures of beautiful Black women, but I intentionally chose light-skinned women with Kinky hair and dark-skinned women with wavy or curly hair. Overwhelmingly, among girls and boys in my class, the darker women (a.k.a. Tatyana Ali, Ananda Lewis, Amerie types) were chosen as the more attractive over lighter-skinned black women that had kinky hair. But overwhelmingly, lighter or mixed-race women who had both light skin AND straighter hair got the highest marks, as expected. (We won’t even go into how body types/shapes play into the ranking system…that’s for another post).

TV Personality Ananda Lewis, Actress/Singer Tatyana Ali; Singer/Songwriter Amerie

Many of the sources I read touched on baby hair, and most of these sources claim that baby hair and laid edges were cultural signifiers for African Americans, not attempts and disguising the true texture of the wearer’s hair. I read essays detailing the history of baby hair in popular culture, Josephine Baker to Bernadette Stanis to Brandy. I watched videos anecdotally detailing Black women’s experiences with learning to do their own and teaching me how to do mine. And while I do appreciate the cultural relevancy of Black brilliance in starting trends and setting pace, I cannot help but think, unpopular as it may be to say, 1) that Baby Hairs, no matter how creative, are rooted in White Supremacy and 2) we are heirs to that bondage.

“Kinky hair is the only thing exclusively indicative of African roots...”

Black Hair is Political

Black Hair is inherently political; there’s no need in denying that, as uncomfortable as it makes me feel. But the politics of Black Hair is an African concept. Hair is communal…doing hair is an integral part of your rites and your rights. The style of your hair indicated your social, economic, and political status. Just as “commoners” were not permitted to wear certain colors in Medieval England (called Sumptuary Laws), certain styles were only reserved for the aristocracy in Black Africa. Historian John Thornton notes that traditional African hairstyling could operate as a way to organize people into social categories, mark important life stages/rites of passage (such as the beginning of puberty or initiation into a group), or serve as parts of religious rituals. The intricacy of effort in your styled hair indicated that someone cared about you. (I believe this “intricacy of effort” was very much at the root of the vitriol a young Blue Ivy met; most felt that “unstyled’ hair signaled a lack of care on her parents’ behalf, when common sense should tell you that is not true. Nevertheless, this very Black concept is still prevalent for Black children in America). Understanding history, however, provides a clearer lens to see SOME of this public outrage through. Emma Dabiri further cites Kobena Mercer as explaining the irony of the “Afro”; the Afro is often interpreted as African when in reality, in West African cultures, hair would never be left “unmolded or unbraided.” The Afro IS a symbol of ”diasporic resistance,” not Africa. (Emphasis added).

“How I grew to believe Black hair has power, genius, and magic in it, defying gravity and limitation. I mean, look at how marvelous it is: Black hair grows up and out.”

Angela Davis, Activist and Author

A History of African Women and Their Hair

While the effort put into styling Black Hair is very African, the effort in Baby Hairs is distinctly African American. HISTORICALLY, looking through the hairstyles of the thousands and thousands of cultural and ethnic groups in Africa, you will not see a Baby Hair in sight. (Colonized Africa is another story.) You will see braids, extensions, accessories, geometric design, gravity-defying feats, floor-sweeping tresses, but no Baby Hair.

Josephine Baker: Plaster of Paris

Now, some of y’all may think what I’m about to say is a reach. But if I’m reaching, it is only because history gave me the stool and I think I have the range. Most sources (that I’ve read) agree that the predecessor to the edge was the wave. Made famous by Josephine Baker, fingerwaves featured precisely the kind of styled structure that came naturally for our ancestors. However, Baker’s styling was more reminiscent of European hair, combining straightened hair, the “conch”, heavy pomade, and small combs to create a sea of wavy perfection, culminating in dainty swirls and curls that rested on the forehead. Ok, here’s the reach: I believe that women like Josephine Baker made this hairstyle as a way to mimic the waves of White hair, while showcasing the malleability of Black hair as a play in exoticism. There. I said it. In order to be successful in Europe, Baker had to show “I’m like you, and I like you, but I’m not like you.” Her hair mimicked her art.

Josephine Baker in her infamous Banana Skirt

Knowing Baker’s background furthers my confidence in the accuracy of these assertions. As a child (yes a child) singing and performing on the Black vaudeville circuit, Baker initially was not favored because she was “too dark” and considered to be not conventionally attractive, with broad buck teeth and long lanky limbs. But she soon proved that she could use her talent for humor, not to overcome colorism, but to circumvent it. She made a name for herself as a chorus line girl, ultimately having her name in lights in marquis of Black theaters across the nation. But eventually, she found that her star could rise no higher here, and so she took her talents to Paris. In the United States, she was considered an oddity, but in Paris, her dark skin, doe-like eyes, sensual hips and “Meg-the-Stallion” knees were an obsession, an exotic glimpse into a world that Parisian society was not accustomed to viewing.

Similar to today, Blackness was in vogue in the early part of the century. We see this in the European obsession with Egypt and African art in general in the early 1900’s. And the same complexion that worked against her in America, gave her more work in Paris, as the “negro” look was in. But even Josephine Baker knew that in spite of her differences, she still needed to provide an air of familiarity. In my opinion, if she had worn her natural hair in its natural state with her natural edges, her brazen sexuality would have played into people’s desire to make Black people savages to be pitied, and not goddesses to be desired as she longed to be and eventually became. After all, Baker was known for the braggadociousness of her sexuality, for playing into and capitalizing off the sexualized tropes of Black women and exploiting the exoticism of her dance and her features for White audiences, all while trying to be just like them. She walked the line of savage and sensual throughout her career, and her hair helped her to do that. Her signature waves and baby hair gave her dark skin an interesting mix of fetish and familiarity to the White patrons that made her a star. (Please do not take this as an unfounded attack on the remarkable women and humanitarian that she was; we can critique those we care about meaningfully). And while we can discuss the potentially problematic nature of representing herself as a monkey or jungle savage in a skirt of bananas another time, it is critical to focus on the lasting fact: Baker’s waves flooded the Black consciousness, and we haven’t seen land since. No one was wearing their hair in that way at the time. Baker’s hair was plastered to perfection; not a kink could be found. Like the plaster of Paris that formed so much of the art and architecture of her adopted homeland, she could mold her hair and her art to be whatever White people wanted. She was chocolate clay. The sleekness and straightness of her hair was familiar, but the structure and style was not, making her a force to be imitated, and then popularly recreated.

Various images of Josephine and her signature style

Some sources have argued that Baby Hair came about as a way for Black people to appear “groomed” and “kempt” to White people. Prior to Baker, Black people in America were only about 40 years removed from legal chattel slavery and were desperately trying to progress. Part of the process was straightening our hair through the use of Marcelle irons, then the straightening comb, then the relaxer, in 1845, 1908 and 1909 respectively. At the turn of the century, idealized Black hair would have been long, straight, and plentiful, piled high a la Gibson girl and adorned with feathers, hats, or other trimming. Authors Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharpe put it this way: “Looking respectable was not just an individual pursuit. At this time in history more so than any other, Blacks were being judged as a monolithic group and the actions or appearance of one was seen as a reflection of the whole…The appearance, including the hair, was the means to a socioeconomic end.” But what Baker did in the 1920’s was special, she took a European ideal and sprinkled some spice on it, and I don’t think it had anything to do with grooming; it had everything to do with texturism. We have anecdotal and empirical evidence that Black people that had more keen features were treated better, had access to better educations, and better jobs. Hair was not just about appearing neat, it was about appearing White.

“Baker’s hair was plastered to perfection; not a kink could be found. Like the plaster of Paris that formed so much of the art and architecture of her adopted homeland, she could mold her hair and her art to be whatever White people wanted. She was chocolate clay...”

Hair styles from the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Ida B. Wells, Anti-lynch Activist and Journalist; A Black woman in the late 1800s, Harriet Gibbs Marshall, first Black Woman to receive a degree in Music from an American Institution (Oberlin College); Nannie Helen Burroughs, Educator, Activists, and Suffragette

Hot Like Chilli

Actress Bernadette Stanis; Actress Jada Pinkett Smith; Actress/Singer Brandy Norwood; Musician/Producer Missy Elliott

Baby Hair has had moments in history where it was not as popular, but it re-emerged in the 70’s as predecessor to the stylized form we see today, even as the first natural hair movement gained traction in popular culture. Instead of fingerwaves, now the emphasis was on the shorter, finer hair around the perimeter of hairlines. We can see this on celebrities like the Jackson girls and Bernadette Stanis. And by the 90’s, we began to see the trend again, although I would argue it was generally in reference to Baker, as seen on Missy Elliot, Jada Pinkett Smith, and any chignon (French Roll) on any Black Auntie on the block.

LaToya and Janet Jackson; The Illustrious French Roll

Until Chilli.

One-third of TLC, Rozanda “Chilli” Thomas’ baby hairs were remarkable and remarked on frequently. We had seen hints of the intricacies in Baby Hair design on Brandy’s braids or Missy’s sideburns, (honorable mention to “Mr. Same Ole’ G Ginuwine), but Chilli was the epitome of baby-hair goals. At the time, this was much easier for us to emulate, as most of us were relaxed. But I have vivid memories of sitting in the mirror with a toothbrush and beeswax, trying relentlessly to find a swoop to swoop.

Cutting Baby Hairs?

Which brings me back to today, sitting on my couch as a 30-something woman, with natural hair and natural questions as to whether or not the art of edges I’m witnessing today is more about culture or conformity. If it was truly about art, would so many naturals relax their edges just to ensure the baby hairs stay baby-ing? Would we see trends such as cutting and curling baby hairs before laying them, so that they appear to be naturally curly instead of artificially plastered? Should we differentiate between the obvious design elements that go into the swirls and swoops intentionally placed in ways to show the skill of Black design, and the desire to style edges to move closer to Whiteness and to self-other yourself?

While trying to formulate thoughts for this think-piece, I remembered an experience I had years ago, while living in Miami during law school. I went to eat at a restaurant with a classmate, who happened to be of Cuban nationality. We were eating outside of Pollo Tropical when this (Black) man approached. He said to us both, “Ohhhh what beautiful mamis do we have here?” (Obviously, the implication was that I was Hispanic…so much ignorance here.) We graciously smiled and continued to eat, but he continued, using strings of Spanglish to try and connect with either of us, actually saying aloud, “I’ll take either one of you, Cuban or Dominican, ‘cause I love me a Spanish chick.” Now, at the time, I didn’t have the lexicon (or the range) to start a discussion on the rampant colorist, featurist, texturist slant of this conversation, so I just said, “I have a man.” (It wasn’t a lie…at the time I did.) And after managing to sho this fly, I turned to my friend and said, “Why would he think I was Hispanic?” Her response between bites of rice was, “Probably your hair.”

She was right. I was relaxed at the time (freshly so) and my edges were swooped to Shango with a wavy bun accomplished by air-drying and lots of mousse. I had set my nape hair in curlers, so that if they were gonna refuse to reach the bun at the top of my head (hello breakage) at least it would be a uniform rebellion. After spending all of this time to make my hair appear to be a different texture than it was, when I was approached differently because of it, I was bothered.

Because I had this nagging question: would he have approached me at all if I hadn’t taken such care to change the texture of my hair?…

Me on the rare occasions where I attempt to style my baby hair.

To be continued in From Jheri to Gina: Catfishing, Curlfishing, and Colorism The Texture of Colorism Part 2

Sources referenced or used:

FTC Disclosure: (Let’s keep things legal and laughing, shall we?) Trust that I only recommend products I use myself or would use myself, books that I own, have read, recommend, and cite. You don’t trust me you say? Well screw it….let’s be honest then. All opinions expressed here are NOT my own because I’m being paid hella green to write these long-ass articles, and read hundreds of books to espouse opinions I don’t even agree with ON TOP OF fulfilling the obligations of a full-time high-school teacher and part-time college professor. This post may contain affiliate links that at no additional cost to you, I may earn a small commission. (And by small commission, I really mean a super-fat check that affords me the ability to fund my villa in Italy and my addiction to Hermes.)

Lol…

Are you still reading? Whew…if you are…you are my people! Now, to really be honest, some of these posts do contain affiliate links, but in reality, you’re just helping me continue to fund this blog and pay off my student loans. So I’d appreciate your support…and if not, I just appreciate you staying this long. Blessings!

Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America by Ayana D. Byrd and Lori L. Tharpe

Don’t Touch My Hair/Twisted: The Tangled History of Black Hair Culture by Emma Dabiri

Josephine Baker’s Last Dance by Sherry Jones